China’s decision to stop taking foreign waste

China has long been the leader in imported recyclable materials, just as it is in much of the world’s international trade. However, the decision by China to no longer accept recyclable imports has sent much of the world into disarray.

On 18 July of last year, China informed the World Trade Organisation that it would ban imports of 24 categories of recyclables and solid waste by the beginning of 2018. The decision has come on the back of the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection’s campaign against ‘foreign garbage’ for the sake of the environment and public health.

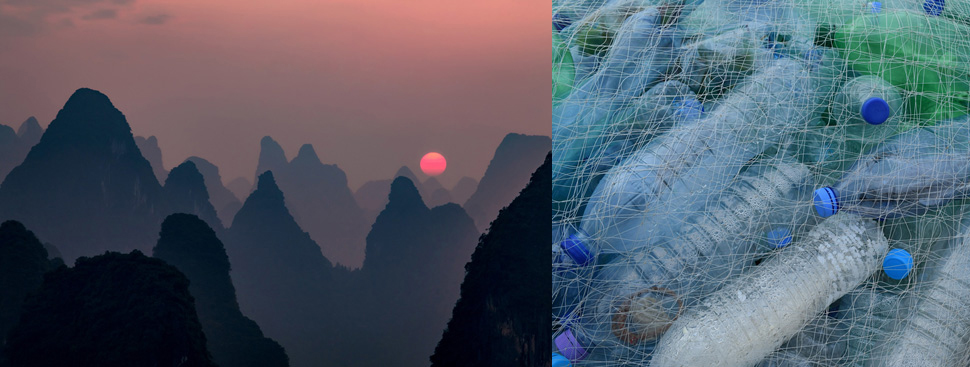

The documentary ‘Plastic China’ focuses on a makeshift recycling plant, located just outside of Qingdao in China. It is one of many remote toxic towns that process the world’s plastic. Impoverished Chinese families work amongst mountains of filthy plastic rubbish, inundated with dirty water, toxic fumes and plastic of all variations.

The impact of the Chinese decision is far-reaching and drastic for many countries across the EU, Asia, the Americas and also for Australia. Considering that China imported an incredible $5 Billion (AU) of foreign rubbish in 2016, billions of dollars of trade will be disrupted,. The decision is expected to cause significant damage to various economies, including the US Dollar, the Euro and the Australian dollar. But the most pressing question for waste recycling and disposal is ‘where does the waste go now?’ Where on earth will the 7.3 million metric tonnes of waste plastic imported by China in 2016 (according to the International Solid Waste Association), go?

There are other options, but none come close to the size of the sink that China has been for receiving foreign waste. South East Asian countries and India are set to massively increase their imports. At home, waste giant Visy has warned China’s decision will help produce “a glut of recyclable materials with ‘no home’.” “The impacts of the China ban are already being experienced, with stockpiling of product in the hope that prices will improve,” Visy said. “This excessive stockpiling is an environmental hazard and significantly increases the risk of fires.”

Visy’s reaction points to the fact that Australia does very little real recycling. The programs we call recycling are really collection programs with the collected products shipped overseas, mainly to China.

In view of this, the dramatic global disruption may be a chance to overhaul a system that desperately needs to be reformed for the sake of our environment. Christine Cole, a staff writer at The Conversation writes, “The problems we are now facing are caused by China’s global dominance in manufacturing and the way many countries have relied on one market to solve their waste and recycling problems.

‘The current situation offers us an opportunity to find new solutions to our waste problem, increase the proportion of recycled plastic in our own manufactured products, improve the quality of recovered materials and to use recycled material in new ways.’

So what happens to the plastic Australia collects through household recycling systems now that China refuses to accept it? Well, the alternatives could completely alter the landscape of our recycling and waste system. The plastic disposal crisis has been simmering away for decades, and now Victoria has an opportunity to respond in a positive manner. Sustainability Victoria estimates it will cost between $3.6 billion and $5 billion in the next 30 years to manage the increase in waste and improve the state’s recycling regime so that less rubbish goes to landfill. With the pressing matter of a closed off China, Victoria is at risk of being overrun by a giant pile of rubbish.

Nina Springle, The Greens waste spokesperson, stated in response to Victoria’s growing waste issue, “It’s time to stop the production of easily disposed of waste products at its source, because people are not regulating themselves. We are consuming so much and we are not thinking about the end product.” It is clear the world cannot continue with the current wasteful consumption model based on infinite growth in a finite world. The new era is not just about effective recycling; it is also about tackling our waste problem at the source, by drastically reducing the production of billions of plastic goods every year.

The call for community action has already been incentivised by one of our neighbours. New South Wales has introduced the NSW Container Deposit Scheme where most drinking containers can be returned for refund of a deposit paid on purchase. Drink container litter makes up 44% of the volume of the state’s litter and costs more than $162 million to manage, according to the NSW EPA. The policy is called ‘Return and Earn’ and it is expected to be a huge part of the Premier’s goal to reduce the volume of litter by 40% by 2020.

The opportunities are obvious, for more jobs, a more stable environmental landscape and better public and community health. Future Recycling’s role is not to present a straight replacement for China. It’d be nice if we had the time, money and resources for such a task! But we are an important piece of the solution. Our infrastructure allows customers to recycle their scrap metal in a safe and environmental friendly way and through our transfer station in Pakenham, all recoverable materials will be recycled and or disposed of in a safe and environmentally responsible manner as well. It is also an essential part of the changing face of waste management and disposal. A movement that sends recyclable materials around and around again.

The opportunities are obvious, for more jobs, a more stable environmental landscape and better public and community health. Future Recycling’s role is not to present a straight replacement for China. It’d be nice if we had the time, money and resources for such a task! But we are an important piece of the solution. Our infrastructure allows customers to recycle their scrap metal in a safe and environmental friendly way and through our transfer station in Pakenham, all recoverable materials will be recycled and or disposed of in a safe and environmentally responsible manner as well. It is also an essential part of the changing face of waste management and disposal. A movement that sends recyclable materials around and around again.

“The real opportunity in Australia is to create that circular economy that’s happening overseas and that’s what China is moving towards, where they’re saying we produce that material, we actually want to recycle that material and reuse it back in the economy,” said Gayle Sloan, the chief executive of the Waste Management Association of Australia (WMAA).

Although the Chinese decision is one that is drastic and overwhelming for countries across the globe, it also presents an almost impassable opportunity to alter the way we consume, minimise our use of unrecyclable plastics, improve the quality of recovered materials and to use recycled material in new ways.

Like China has done in its own backyard, it could be the perfect chance to consider just how vital our waste and recycling system is for our environment, our public health and our very future.

Comments are closed.